*** Proof of Product ***

Exploring the Essential Features of “Richard Wolfson – Physics and Our Universe”

Physics and Our Universe

An award-winning professor brings physics down to earth from everyday examples to universal principles.

LECTURE (60)

01:The Fundamental Science

Take a quick trip from the subatomic to the galactic realm as an introduction to physics, the science that explains physical reality at all scales. Professor Wolfson shows how physics is the fundamental science that underlies all the natural sciences. He also describes phenomena that are still beyond its explanatory power.

02:Languages of Physics

Understanding physics is as much about language as it is about mathematics. Begin by looking at how ordinary terms, such as theory and uncertainty, have a precise meaning in physics. Learn how fundamental units are defined. Then get a taste of the basic algebra that is used throughout the course.

03:Describing Motion

Motion is everywhere, at all scales. Learn the difference between distance and displacement, and between speed and velocity. Add to these the concept of acceleration, which is the rate of change of velocity, and you are ready to delve deeper into the fundamentals of motion.

04:Falling Freely

Use concepts from the previous lecture to analyze motion when an object is under constant acceleration due to gravity. In principle, the initial conditions in such cases allow the position of the object to be determined for any time in the future, which is the idea behind Isaac Newton’s “clockwork universe.”

05:It’s a 3-D World!

Add the concept of vector to your physics toolbox. Vectors allow you to specify the magnitude and direction of a quantity such as velocity. The vector’s direction can be along any axis, allowing analysis of motion in three dimensions. Then use vectors to solve several problems in projectile motion.

06:Going in Circles

Circular motion is accelerated motion, even if the speed is constant, because the direction, and hence the velocity, is changing. Analyze cases of uniform and non-uniform circular motion. Then close with a problem challenging you to pull out of a dive in a jet plane without blacking out or crashing.

07:Causes of Motion

For most people, the hardest part of learning physics is to stop thinking like Aristotle, who believed that force causes motion. It doesn’t. Force causes change in motion. Learn how Galileo’s realization of this principle, and Newton’s later formulation of his three laws of motion, launched classical physics.

08:Using Newton’s Laws-1-D motion

Investigate Newton’s second law, which relates force, mass, and acceleration. Focus on gravity, which results in a force, called weight, that’s proportional to an object’s mass. Then take a ride in an elevator to see how your measured weight changes due to acceleration during ascent and descent.

09:Action and Reaction

According to Newton’s third law, “for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.” Professor Wolfson has a clearer way of expressing this much-misunderstood phrase. Also, see several demonstrations of action and reaction, and learn about frictional forces through examples such as antilock brakes.

10:Newton’s Laws in 2 and 3 Dimensions

Consider Newton’s laws in cases of two and three dimensions. For example, how fast does a rollercoaster have to travel at the top of a loop to keep passengers from falling out? Is there a force pushing passengers up as the coaster reaches the top of its arc? The answer may surprise you.

11:Work and Energy

See how the precise definition of work leads to the concept of energy. Then explore how some forces “give back” the work done against them. These conservative forces lead to the concept of stored potential energy, which can be converted to kinetic energy. From here, develop the important idea of conservation of energy.

12:Using Energy Conservation

A dramatic demonstration with a bowling ball pendulum shows how conservation of energy is a principle you can depend on. Next, solve problems in complicated motion using conservation of energy as a shortcut. Close by drawing the distinction between energy and power, which are often confused.

13:Gravity

Newton realized that the same force that makes an apple fall to the ground also keeps the moon in its orbit around Earth. Explore this force, called gravity, by focusing on circular orbits. End by analyzing why an orbiting spacecraft has to decrease its kinetic energy in order to speed up.

14:Systems of Particles

How do you analyze a complex system in motion? One special point in the system, called the center of mass, reduces the problem to its simplest form. Also learn how a system’s momentum is unchanged unless external forces act on it. Then apply the conservation of momentum principle to analyze inelastic and elastic collisions.

15:Rotational Motion

Turn your attention to rotational motion. Rotational analogs of acceleration, force, and mass obey a law related to Newton’s second law. This leads to the concept of angular momentum and the all-important -conservation of angular momentum, which explains some surprising and seemingly counterintuitive phenomena involving rotating objects.

16:Keeping Still

What’s the safest angle to lean a ladder against a wall to keep the ladder from slipping and falling? This is a problem in static equilibrium, which is the state in which no net force or torque (rotational force) is acting. Explore this condition and develop tools for determining whether equilibrium is stable or unstable.

17:Back and Forth-Oscillatory Motion

Start a new section in which you apply Newtonian mechanics to more complex motions. In this lecture, study oscillations, a universal phenomenon in systems displaced from equilibrium. A special case is simple harmonic motion, exhibited by springs, pendulums, and even molecules.

18:Making Waves

Investigate waves, which transport energy but not matter. When two waves coexist at the same point, they interfere, resulting in useful and surprising applications. Also examine the Doppler effect, and see what happens when an object moves through a medium faster than the wave speed in that medium.

19:Fluid Statics-The Tip of the Iceberg

Fluid is matter in a liquid or gaseous state. In this lecture, study the characteristics of fluids at rest. Learn why water pressure increases with depth, and air pressure decreases with height. Greater pressure with depth causes buoyancy, which applies to balloons as well as boats and icebergs.

20:Fluid Dynamics

Explore fluids in motion. Energy conservation requires low pressure where fluid velocity is high, and vice versa. This relation between pressure and velocity results in many practical and sometimes counterintuitive phenomena, collectively called the Bernoulli effect-explaining why baseballs curve and how airplane speedometers work.

21:Heat and Temperature

Beginning a new section, learn that heat is a flow of energy driven by a temperature difference. Temperature can be measured with various techniques but is most usefully quantified on the Kelvin scale. Investigate heat capacity and specific heat, and solve problems in heating a house and cooling a nuclear reactor.

22:Heat Transfer

Analyze heat flow, which involves three important heat-transfer mechanisms: conduction, which results from direct molecular contact; convection, involving the bulk motion of a fluid; and radiation, which transfers energy by electromagnetic waves. Study examples of heat flow in buildings and in the sun’s interior.

23:Matter and Heat

Heat flow into a substance usually raises its temperature. But it can have other effects, including thermal expansion and changes between solid, liquid, and gaseous forms-collectively called phase changes. Investigate these phenomena, starting with an experiment in which Professor Wolfson pours liquid nitrogen onto a balloon filled with air.

24:The Ideal Gas

Delve into the deep link between thermodynamics, which looks at heat on the macroscopic scale, and statistical mechanics, which views it on the molecular level. Your starting point is the ideal gas law, which approximates the behavior of many gases, showing how temperature, pressure, and volume are connected by a simple formula.

25:Heat and Work

The first law of thermodynamics relates the internal energy of a system to the exchange of heat and mechanical work. Focus on isothermal (constant temperature) and adiabatic (no heat flow) processes, and see how they apply to diesel engines and the atmosphere.

26:Entropy-The Second Law of Thermodynamics

Turn to an idea that has been compared to a work of Shakespeare: the second law of thermodynamics. According to the second law, entropy, a measure of disorder, always increases in a closed system. Order can only increase at the cost of even greater entropy elsewhere in the system.

27:Consequences of the Second Law

The second law puts limits on the efficiency of heat engines and shows that humankind’s energy use could be better planned. Learn why it makes sense to exploit low-entropy, high-quality energy for uses such as transportation, motors, and electronics, while using high-entropy random thermal energy for heating.

28:A Charged World

Embark on a new section of the course, devoted to electromagnetism. Begin by investigating electric charge, which is a fundamental property of matter. Coulomb’s law states that the electric force depends on the product of the charges and inversely on the square of the distance between them.

29:The Electric Field

On of the most important ideas in physics is the field, which maps the presence and magnitude of a force at different points in space. Explore the concept of the electric field, and learn how Gauss’s law describes the field lines emerging from an enclosed charge.

30:Electric Potential

Jolt your understanding of electric potential difference, or voltage. A volt is one joule of work or energy per coulomb of charge. Survey the characteristics of voltage-from batteries, to Van de Graaff generators, to thunderstorms, which discharge lightning across a potential difference of millions of volts.

31:Electric Energy

Study stored electric potential energy in fuels such as gasoline, where the molecular bonds represent an enormous amount of energy ready to be released. Also look at a ubiquitous electronic component called the capacitor, which stores an electric charge, and discover that all electric fields represent stored energy.

32:Electric Current

Learn the definition of the unit of electric current, called the ampere, and how Ohm’s law relates the current in common conductors to the voltage across the conductor and the conductor’s resistance. Apply Ohm’s law to a hard-starting car, and survey tips for handling electricity safely.

33:Electric Circuits

All electric circuits need an energy source, such as a battery. Learn what happens inside a battery, and analyze simple circuits in series and in parallel, involving one or more resistors. When capacitors are incorporated into circuits, they store electric energy and introduce time dependence into the circuit’s behavior.

34:Magnetism

In this introduction to magnetism, discover that magnetic phenomena are really about electricity, since magnetism involves moving electric charge. Learn the right-hand rule for the direction of magnetic force. Also investigate how a current-carrying wire in a magnetic field is the principle behind electric motors.

35:The Origin of Magnetism

No matter how many times you break a magnet apart, each piece has a north and south pole. Why? Search for the origin of magnetism and learn how magnetic field lines differ from those of an electric field, and why Earth has a magnetic field.

36:Electromagnetic Induction

Probe one of the most fascinating phenomena in all of physics, electromagnetic induction, which shows the direct relationship between electric and magnetic fields. In a demonstration with moving magnets, see how the relative motion of a magnet and an electric conductor induces current in the conductor.

37:Applications of Electromagnetic Induction

Survey some of the technologies that exploit electromagnetic induction: the electric generators that supply nearly all the world’s electrical energy, transformers that step voltage up or down for different uses, airport metal detectors, microphones, electric guitars, and induction stovetops, among many other applications.

38:Magnetic Energy

Study the phenomenon of self-inductance in a solenoid coil, finding that the magnetic field within the coil is a repository of magnetic energy, analogous to the electric energy stored in a capacitor. Close by comparing the complementary aspects of electricity and magnetism.

39:AC/DC

Direct current (DC) is electric current that flows in one direction; alternating current (AC) flows back and forth. Learn how capacitors and inductors respond to AC by alternately storing and releasing energy. Combining a capacitor and inductor in a circuit provides the electrical analog of simple harmonic motion introduced in Lecture 17.

40:Electromagnetic Waves

Explore the remarkable insight of physicist James Clerk Maxwell in the 1860s that changing electric fields give rise to magnetic fields in the same way that changing magnetic fields produce electric fields. Together, these changing fields result in electromagnetic waves, one component of which is visible light.

41:Reflection and Refraction

Starting a new section of the course, discover that light often behaves as rays, which change direction at boundaries between materials. Investigate reflection and refraction, answering such questions as, why doesn’t a dust mote block data on a CD? How do mirrors work? And why do diamonds sparkle?

42:Imaging

See how curving a mirror or a piece of glass bends parallel light rays to a focal point, allowing formation of images. Learn how images can be enlarged or reduced, and the difference between virtual and real images. Use your knowledge of optics to solve problems in vision correction.

43:Wave Optics

Returning to themes from Lecture 18 on waves, discover that when light interacts with objects comparable in size to its wavelength, then its wave nature becomes obvious. Examine interference and diffraction, and see how these effects open the door to certain investigations, while hindering others.

44:Cracks in the Classical Picture

Embark on the final section of the course, which covers the revolutionary theories that superseded classical physics. Why did classical physics need to be replaced? Discover that by the late 19th century, inexplicable cracks were beginning to appear in its explanatory power.

45:Earth, Ether, Light

Review the famous Michelson-Morley experiment, which was designed to detect the motion of Earth relative to a conjectured “ether wind” that supposedly pervaded all of space. The failure to detect any such motion revealed a deep-seated contradiction at the heart of physics.

46:Special Relativity

Discover the startling consequences of Einstein’s principle of relativity-that the laws of physics are the same for all observers in uniform motion. One result is that the speed of light is the same for all observers, no matter what their relative motion-an idea that overturns the concept of simultaneity.

47:Time and Space

Einstein’s special theory of relativity upends traditional notions of space and time. Solve the simple formulas that show the reality of time dilation and length contraction. Conclude by examining the twins paradox, discovering why one twin who travels to a star and then returns ages more slowly than the twin back on Earth.

48:Space-Time and Mass-Energy

In relativity theory, contrary to popular views, reality is what’s not relative-that is, what doesn’t depend on one’s frame of reference. See how space and time constitute one such pair, merging into a four-dimensional space-time. Mass and energy similarly join, related by Einstein’s famous E = mc2.

49:General Relativity

Special relativity is limited to reference frames in uniform motion. Following Einstein, make the leap to a more general theory that encompasses accelerated frames of reference and necessarily includes gravity. According to Einstein’s general theory of relativity, gravity is not a force but the geometrical structure of spacetime.

50:Introducing the Quantum

Begin your study of the ideas that revolutionized physics at the atomic scale: quantum theory. The word “quantum” comes from Max Planck’s proposal in 1900 that the atomic vibrations that produce light must be quantized-that is, they occur only with certain discrete energies.

51:Atomic Quandaries

Apply what you’ve learned so far to work out the details of Niels Bohr’s model of the atom, which patches one of the cracks in classical physics from Lecture 44. Although it explains the energies of photons emitted by simple atoms, Bohr’s model has serious limitations.

52:Wave or Particle?

In the 1920s physicists established that light and matter display both wave- and particle-like behavior. Probe the nature of this apparent contradiction and the meaning of Werner Heisenberg’s famous uncertainty principle, which introduces a fundamental indeterminacy into physics.

53:Quantum Mechanics

In 1926 Erwin Schrödinger developed an equation that underlies much of our modern quantum-mechanical description of physical reality. Solve a simple problem with the Schrödinger equation. Then learn how the merger of quantum mechanics and special relativity led to the discovery of antimatter.

54:Atoms

Drawing on what you now know about quantum mechanics, analyze how atoms work, discovering that the electron is not a point particle but behaves like a probability cloud. Investigate the exclusion principle, and learn how quantum mechanics explains the periodic table of elements and the principle behind lasers.

55:Molecules and Solids

See how atoms join to make molecules and solids, and how this leads to the quantum effects that underlie semiconductor electronics. Also probe the behavior of matter in ultradense white dwarfs and neutron stars, and learn how a quantum-mechanical pairing of electrons at low temperatures produces superconductivity.

56:The Atomic Nucleus

In the first of two lectures on nuclear physics, study the atomic nucleus, which consists of positively charged protons and electrically neutral neutrons, held together by the strong nuclear force. Many combinations of protons and neutrons are unstable; such nuclei are radioactive and decay with characteristic half lives.

57:Energy from the Nucleus

Investigate nuclear fission, in which a heavy, unstable nucleus breaks apart; and nuclear fusion, where light nuclei are joined. In both, the released energy is millions of times greater than the energy from chemical reactions and comes from the conversion of nuclear binding energy to kinetic energy.

58:The Particle Zoo

By 1960 a myriad of seeming elementary particles had been discovered. Survey the standard model that restored order to this subatomic chaos, describing a universe whose fundamental particles include six quarks; the electron and two heavier cousins; elusive neutrinos; and force-carrying particles such as the photon.

59:An Evolving Universe

Trace the discoveries that led astronomers to conclude that the universe began some 14 billion years ago in a big bang. Detailed measurements of the cosmic microwave background and other observations point to an initial period of tremendous inflation, followed by slow expansion and an as-yet inexplicable accelerating phase.

60:Humble Physics-What We Don’t Know

Having covered the remarkable discoveries in physics, turn to the great gap in our current knowledge, namely the nature of the dark matter and dark energy that constitute more than 95% of the universe. Close with a look at other mysteries that physicists are now working to solve.

DETAILS

Overview

Discover the beauty and simplicity of science’s most fundamental branch with Physics and Our Universe: How It All Works. Intensively illustrated with diagrams, experiments, animations, graphs, and other visual aids, these 60 lectures by engaging and award-winning Professor Richard Wolfson introduce you to scores of fundamental ideas such as Newtonian mechanics, waves and fluids, thermodynamics, electricity and magnetism, optics, and relativity and quantum theory.

About

Richard Wolfson

Physics explains the workings of the universe at the deepest level, the everyday natural phenomena that are all around us, and the technologies that enable modern society. It’s an essential liberal art.

ALMA MATER

Dartmouth College

INSTITUTION

Middlebury College

Dr. Richard Wolfson is the Benjamin F. Wissler Professor of Physics at Middlebury College, where he also teaches Climate Change in Middlebury’s Environmental Studies Program. He completed his undergraduate work at MIT and Swarthmore College, graduating from Swarthmore with a double major in Physics and Philosophy. He holds a master’s degree in Environmental Studies from the University of Michigan and a Ph.D. in Physics from Dartmouth.

Professor Wolfson’s published work encompasses diverse fields such as medical physics, plasma physics, solar energy engineering, electronic circuit design, observational astronomy, theoretical astrophysics, nuclear issues, and climate change. His current research involves the eruptive behavior of the sun’s outer atmosphere, or corona, as well as terrestrial climate change and the sun-Earth connection.

Professor Wolfson is the author of several books, including the college textbooks Physics for Scientists and Engineers, Essential University Physics,and Energy, Environment, and Climate. He is also an interpreter of science for the nonspecialist, a contributor to Scientific American, and author of the books Nuclear Choices: A Citizen’s Guide to Nuclear Technology and Simply Einstein: Relativity Demystified.

Please see the full list of alternative group-buy courses available here: https://lunacourse.com/shop/

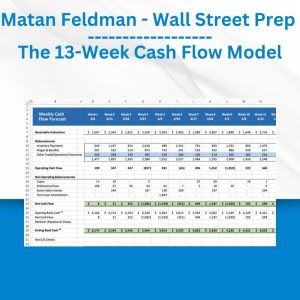

Matan Feldman - The 13-Week Cash Flow Modeling - Wall Street Prep

Matan Feldman - The 13-Week Cash Flow Modeling - Wall Street Prep  Racing Workshop - Complete Online Package

Racing Workshop - Complete Online Package  SMB - Options Training

SMB - Options Training  Atlas API Training - API 570 Exam Prep Training Course

Atlas API Training - API 570 Exam Prep Training Course  Forexmentor - Recurring Forex Patterns

Forexmentor - Recurring Forex Patterns  The Daily Traders – Exclusive Trading Mentorship Group

The Daily Traders – Exclusive Trading Mentorship Group  Trade Like Mike - The TLM Playbook 2022

Trade Like Mike - The TLM Playbook 2022  Simpler Trading - Bruce Marshall - The Options Defense Course

Simpler Trading - Bruce Marshall - The Options Defense Course  Money Miracle - George Angell - Use Other Peoples Money To Make You Rich

Money Miracle - George Angell - Use Other Peoples Money To Make You Rich  Erik Banks - Alternative Risk Transfer

Erik Banks - Alternative Risk Transfer  Sovereign Man Confidential - Renunciation Video

Sovereign Man Confidential - Renunciation Video  Julie Stoian & Cathy Olson - Launch Gorgeous - Funnel Gorgeous Bundle

Julie Stoian & Cathy Olson - Launch Gorgeous - Funnel Gorgeous Bundle  Akil Stokes & Jason Graystone - TierOneTrading - Trading Edge 2019

Akil Stokes & Jason Graystone - TierOneTrading - Trading Edge 2019  Michael Mithoefer - Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy In-depth: In-session demonstrations and real-world insight into MDMA & more

Michael Mithoefer - Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy In-depth: In-session demonstrations and real-world insight into MDMA & more  Biochemistry and Molecular Biology: How Life Works - Kevin Ahern

Biochemistry and Molecular Biology: How Life Works - Kevin Ahern  Crypto Dan - The Crypto Investing Blueprint To Financial Freedom By 2025

Crypto Dan - The Crypto Investing Blueprint To Financial Freedom By 2025  Jane Roberts - The Seth MP3 #18 - Digital Download - Seth Center

Jane Roberts - The Seth MP3 #18 - Digital Download - Seth Center  Scott Benedict - COMPREHENDED! 2021

Scott Benedict - COMPREHENDED! 2021  Jim Donavan - Memory Sound Supplement

Jim Donavan - Memory Sound Supplement  Steven Shadow - The Perfect Seduction

Steven Shadow - The Perfect Seduction  Matthew Kratter - Trader University

Matthew Kratter - Trader University  Alphashark - The AlphaShark SV-Scalper

Alphashark - The AlphaShark SV-Scalper  GOATA Movement Blueprint

GOATA Movement Blueprint  Rajandran R - Practical Approach to Amibroker AFL Coding

Rajandran R - Practical Approach to Amibroker AFL Coding  Greg Loehr - Advanced Option Trading With Broken Wing Butterflies

Greg Loehr - Advanced Option Trading With Broken Wing Butterflies  The Geometric Trading Course - Apprentice Level II

The Geometric Trading Course - Apprentice Level II  Maven Analytics, Chris Dutton & Aaron Parry - Microsoft Power BI Desktop for Business Intelligence (2023)

Maven Analytics, Chris Dutton & Aaron Parry - Microsoft Power BI Desktop for Business Intelligence (2023)  Fred Haug - Virtual Wholesaling Simplified

Fred Haug - Virtual Wholesaling Simplified  Lara Adler - The Certificate Course in Environmental Health

Lara Adler - The Certificate Course in Environmental Health  George Fontanills & Tom Gentile - Optionetics Wealth Without Worry Course

George Fontanills & Tom Gentile - Optionetics Wealth Without Worry Course  Team NFT Money - Ultimate NFT Playbook

Team NFT Money - Ultimate NFT Playbook  David Cavanagh – YouTube Internet Secrets Revealed

David Cavanagh – YouTube Internet Secrets Revealed  Michael Carroll - Close That Sale

Michael Carroll - Close That Sale  Advanced MMXM – The Inner Circle Dragons

Advanced MMXM – The Inner Circle Dragons  Bessel van der Kolk - The Traumatic Impact of a Global Pandemic and How it will Shape Patient Care in the Future - PESI

Bessel van der Kolk - The Traumatic Impact of a Global Pandemic and How it will Shape Patient Care in the Future - PESI